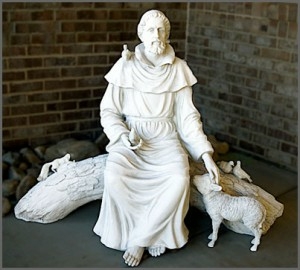

The statue of St. Francis by our front door

Even people who don’t know much about St. Francis know that he had a special bond with animals and birds. They may not have heard of the wolf of Gubbio, but they’ve seen garden statues of Francis with birds on his shoulders and may have even brought their family dog, cat, or hamster to one of the many “Blessing of the Animals” services sponsored by Catholic and Protestant churches.

If you associate Francis with animals, you probably also assume that all Franciscans love animals and birds.

That’s a safe assumption where this community of Poor Clares is concerned!

You don’t have to spend much time outside the monastery, or inside, or with the sisters to discover the depth of our love of nature and God’s wonderful creatures in particular.

As you turn off McCauley Road onto the monastery property, you’ll notice wide areas of wildflowers and tall grass that we keep unmowed in order to provide natural habits for birds and small mammals. In the morning and late afternoon, you’ll find rabbits nibbling on the clover, groundhogs exploring the taller grass, chipmunks scurrying under shrubs, deer grazing near the woods, and the occasional fox trotting purposefully across the lawn.

Birds (and the occasional squirrel) can usually find a snack at the monastery

Look closely at the windows facing the road, and you’ll see a variety of bird feeders, with bird baths nestled in the ground or placed nearby.

As you approach our front door, look up, and you may see birds’ nests tucked into the overhangs. What you may not notice are the sets of binoculars resting on windowsills near those nests. The sisters keep a close eye on nesting birds and hatchlings.

Of course, we also have a statue of St. Francis by our front door. He’s sitting with a lamb by his side, a bird on his shoulder, and a bird in his hand. Small children love to sit on the bench or the ground next to him, providing their parents with sweet photo opportunities. (We’ve received copies of many photographs of children sitting with Francis!) This past week, a visiting Labradoodle puppy bounded up to the statue and licked it happily, proving that young ones of many species find a friend in Francis.

We don’t have any pets of our own, but we are on friendly terms with numerous critters who live in the courtyards and gardens within our cloister. We know, and in a few cases have named, the frogs and toads that inhabit our kitchen garden; on bright days, we also watch for the lizards that like to sun themselves outside the Blessed Sacrament Chapel. We recognize the mockingbirds who’ve claimed the territory outside our dining room and know which hummingbirds prefer which feeder.

Each sister has her favorites. Some don’t share my great love of squirrels (although I am trying to change minds), and while we have one sister with a keen interest in and encyclopedic knowledge of entomology, we don’t all share her fascination with bugs. Some sisters prefer to maintain a somewhat-greater-than-normal distance from snakes and spiders, but generally, we strive to live in peaceful co-existence with the creatures who share this land with us.

We were delighted to welcome Bishop Robert and his dog Barney to the monastery last week!

We take delight, too, in our neighbors’ animals: Squirt, the donkey, and his equine and canine companions, and the other horses, ponies, goats, sheep, ducks, geese, and dogs that live around us. And we fondly remember the flock of guinea hens who used to visit us daily and hope that a neighbor will adopt more someday soon.

The delight we take in these living creatures is surely only a shadow of the delight that God takes in His creation. What would it mean if we could see not only other people but also all forms of life with such love and delight? Could we even use words like “weeds” and “pests” if we had that vision?

We cannot see as God sees, for in this life, we can only see through a glass, darkly. We can, however, marvel at God’s creatures and show gratitude for them. We can follow Francis and see all creatures as our brothers and sisters; we can praise God who is the common Father of all that is living.

We can, with Gerard Manley Hopkins, proclaim that “The world is charged with the grandeur of God” (from “God’s Grandeur”). Hopkins, though a Jesuit, was heavily influenced by the writings of Duns Scotus, and there is certainly a Franciscan quality to his poetry. His poem “Pied Beauty” is a hymn of praise for the wonders of God’s creation and humankind’s contributions to this creation. “Glory be to God for dappled things,” he begins; he concludes by acclaiming

All things counter, original, spare, strange;

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim;

He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change:

Praise Him.